I quit smoking fourteen years and one month ago. I was 33. Most of my smoking friends, including my best friend and roommate, had recently moved away. My favorite bar had gone non-smoking. The state would be fully non-smoking by Christmas. And when one of my other best, still-smoking friends announced to me, on a September midnight highway, as we drove home from a Bruce Springsteen concert (where we’d literally missed the first half of “Born To Run” on account of going outside to smoke a cigarette), that she was actively taking steps to quit. I felt disappointed and envious. I watched my smoke curl out the window and mingle with the fog at the I-26 edge of the world climbing up the Eastern Continental Divide and thought, “It’s time for me to be done with this.”

Two and a half weeks, one prescription for Wellbutrin, and a couple of white-knuckled days of chewing Nicorette and rewatching “Local Hero” until the urge settled, I was shockingly, painfully, weirdly done with cigarettes. I want to tell you that I felt proud of myself. I did not. There was a touch of embarrassment that I hadn’t quit earlier, but I knew I’d picked the best and worst possible time for it. And not just because I’d already planned and invited people to a “Mad Men” themed Halloween Party (remember 2009?) at the end of October. The conditions that allowed me to quit easily were also the ones that made quitting seem absurd. To wit: the sudden, perplexing, all-at-once evaporation of my social network, the lack of people to go do things with (at smoking or non-smoking venues), and the very painful, crushing sense that they’d all moved, if not on from me, then to something grander and better, and that I was too weak or too stupid or too cowardly to know when to walk away from the drowsy, broke, neighborly existence I cherished. Most of them were younger than I was, after all. What the fuck was wrong with me that this was all I seemed to want?

In my experience there was no better companion to existential desolation than a pack of Camel Lights. I spent a lot of time that fall imagining that I might wander up the street to the bar or over to the convenience store and just buy a pack. I didn’t. I stopped wandering up the street for much of anything. I stopped going outside without a reason to wander out and stand in the cold and contemplate the stars through the haze of my own worst habit. I tried whiskey, which made me cry and write very maudlin short stories about beautiful terrible men. And pot, which made me sleepy and woozy. I stayed on the antidepressants, which never really made me feel better than depressed, but I worried if I stopped I’d feel even worse. I started running, then running a lot and further. I got sadder, but time passed, seasons, years. The waters did not calm so much as I stopped noticing the undertow. I got used to swimming against the drag. I was less sad. I made new friends that did not smoke. Or at least did not smoke anymore. I only thought about smoking when I dreamed. In my dreams, I was still a smoker.

>>>

My grandmother was a smoker.

Scratch that. Both of my grandmothers were smokers. The paternal WASPy one, who responded to her Christian name without any grandmotherly appendage, quit smoking in her early 70s, after a brush with stomach cancer forced her to reconsider her various addictions. Smoking, for her, was more easily abandoned than gin and tonics.

But I’m really talking about Nana, my maternal grandmother, my sparkly, opinionated, perennially complicated lodestone of unconditional love (may she rest in peace). Nana smoked until the day she died, at the age of 93, from congestive heart failure and complications from COPD. Nana handled a Virginia Slim Ultra Light like a magic wand. The cigarette was so inevitable that it might as well have been an additional appendage. The smoldering tip glowing like another gemstone on her finger. She argued vociferously for the health benefits of smoking. She yelled at restaurant employees who tried to enforced smoking sections. She laughed at doctors. She sneaked cigarettes into the hospital. She is maybe the reason why they had to put the sign in airplanes about smoking in the lavatories. Phillip Morris should have put her on payroll. When my mother busted me sitting at home, feet on the coffee table, smoking a pack of camels in flagrante delicto at seventeen when I was supposed to be recuperating on a sick day, Nana not only didn’t scold, but gave me an antique fillagree-d cigarette case told me she was thrilled I could finally smoke with her.

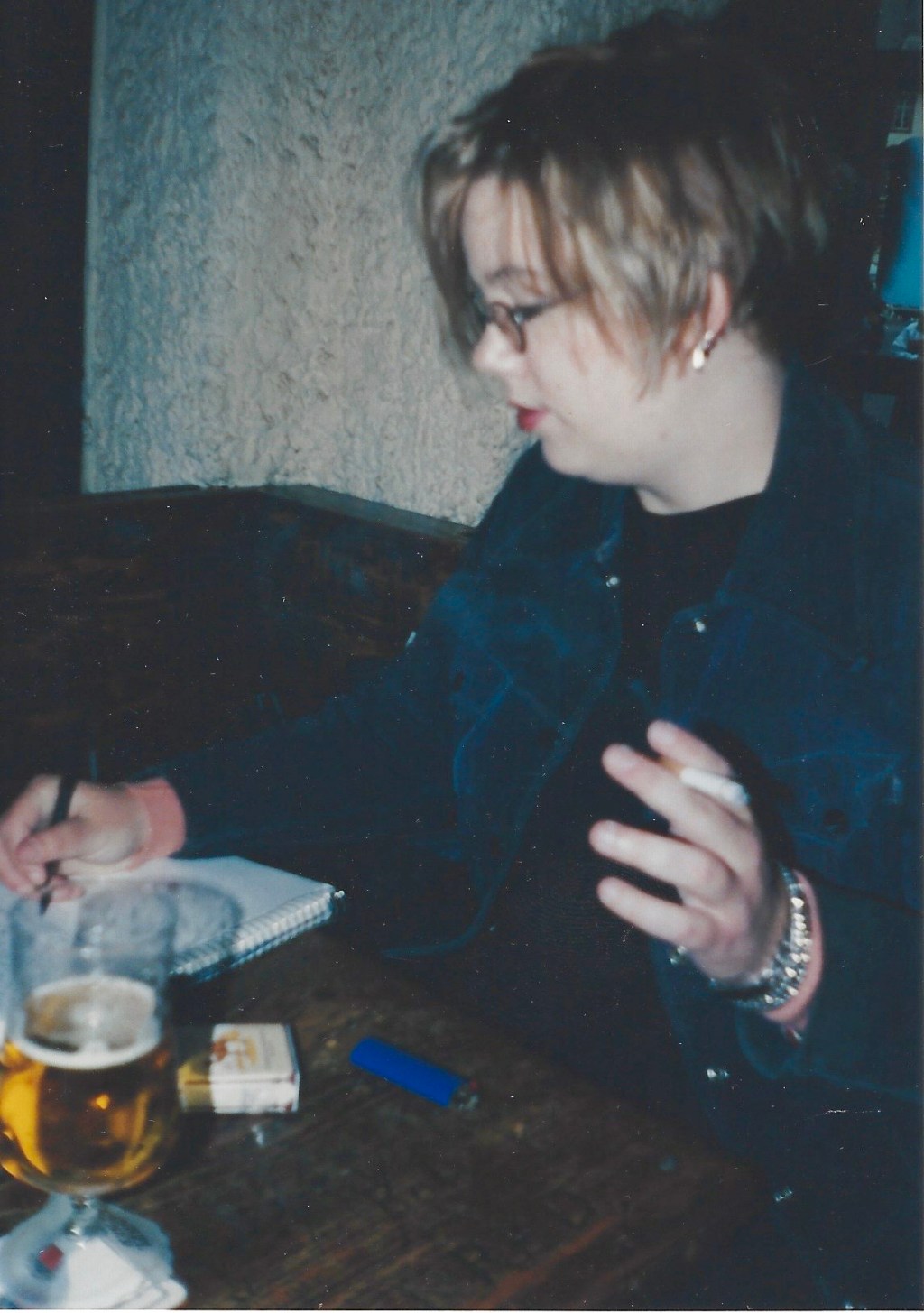

Cigarettes were an easily enough commodity to acquire in the early 1990s, even without Nana’s encouragement. Smoking was just a thing that everyone did. Especially everyone young. It’s how you made friends. It’s how you talked to crushes. Bumming a cigarette was the easiest way to initiate conversation. It’s how you announced the world, as much as anything else, that you probably weren’t a bible thumper, a narc, or a electively bald dude that was going to quote Henry Rollins at you. I went to a school where smoking was, at least theoretically, an expulsion offense and I only had one high school friend that didn’t smoke. She was a genius, so we didn’t give her a hard time. Smart people and their eccentricities and all.

This is not, in any way, to defend the smoking, or to lionize it. Or suggest that it wasn’t a scourge of bad air and stale clothes and public health. But you can feel nostalgia for things that are bad for you (John Hughes movies, bad relationships, worse infatuations, random hookups, watching the sun come up as you walk home from a party, underachievement, justifying your underacheivement with some bullshit about not selling out, secretly believing you might be a genius, that you might have the kind of talent to make it, really make it, even as the years catch up with you and hey, you have no savings and suddenly your old punk rock friends are doctors or lawyers or talking about buying a boat. Shit). I’m not going to hate myself because I once liked smoking. I’m not even inclined to hate myself for missing smoking The simplicity of it. The comfort. The edgy clarity it would add to mornings. The way it would animate conversations all night. How it would for a moment, like magic, make me believe I could handle it. It being everything. It being nothing. It being the full spectrum, light to dark, but mostly gray like smoke.

>>>

I always told people that come the end of the world, I would start smoking again. If my time was up, if we were just going to end, if there was no time left. On Election Night 2016, I wore a pantsuit to a party with a bunch of librarians and lawyers, and expected that I would celebrate the election of the first female president with a glass of champagne. Three hours later, I drank a juice glass of whiskey and bummed my first cigarette in seven years because I thought a slide into fascism might warrant it. I didn’t enjoy the cigarette. Even if it hadn’t tasted like burning tires and wooze, it didn’t really ameliorate the sense of defeat. It just made me feel like I was a sucker with no willpower rearranging ashtrays on the edge of middle age in a failing state.

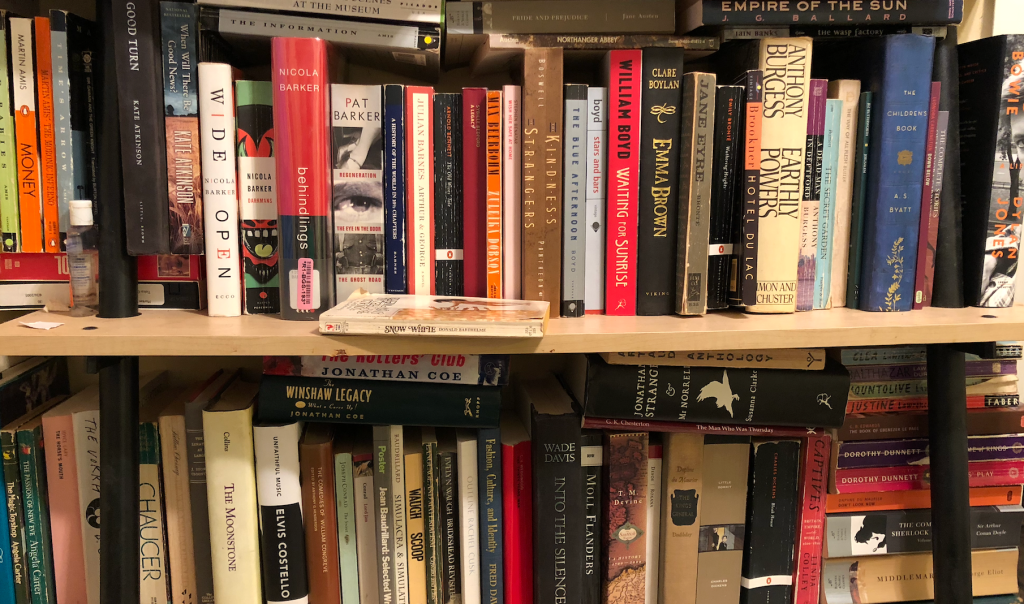

Until I moved, back in 2020, I was close enought to downtown bar that I figured I’d have enough time enough to scoot up for a pack of cigarettes before the nuclear bomb hit. But until 2020, I don’t think I really considered the actual reality of an apocalyptic scenario. And then a pandemic hit and I was like, “Huh. Is this it?” And then Nana died during a global pandemic, and I felt adrift and lost and in position of her fancy Waterford ashtrays that I can’t bear to give away (one of them sits on my desk and holds my business cards. I swear to God that isn’t a metaphor) . And then there was an attempted coup. And then there was war and climate disaster. And then there was bigger war and terrible politics and worst injustice and more war. And then after losing years to anxiety and solitude,I woke up one day and realized I was lonely and fat and didn’t look the slightest bit like Cate Blanchett and was not getting any younger and quite unsatisfied, even blue, even teetering on the kind of desolation that comes with realizing the end, the end that has always felt more like a rhetorical device than an inevitability, might actually be an end. And the tragedy was I didn’t even want a cigarette. In fact, couldn’t think of a single real, tangible, possible thing—not travel, not parties, not fancy cheese, or music, or books, or Beyonce- that would make me feel better.

It’s been a not-great season. I’m not even talking about the over-arching grimness of national or global affairs. I’m talking personal, personal enough that I know how petty it is to talk so much about it. It’s mostly just bad luck. Rotting floorboards bad luck. Sick cat bad luck. “I’m seriously having a Paxlovid rebound on a week of multiple birthdays after a touch of Covid, which I managed to avoid for 3.5 years until I was on vacation” bad luck. None of what is happening to me is a big deal. The whole of it sucks, the old undertow, and the sands of shifted again. I’ll get over it. I’ll test negative. I’ll start running again. I’ll take up sit-ups or meditation or whatever people do when even the good stuff feels hollow. The season will pass. Then another. Something will spark around the corner. Someone will offer me a light.