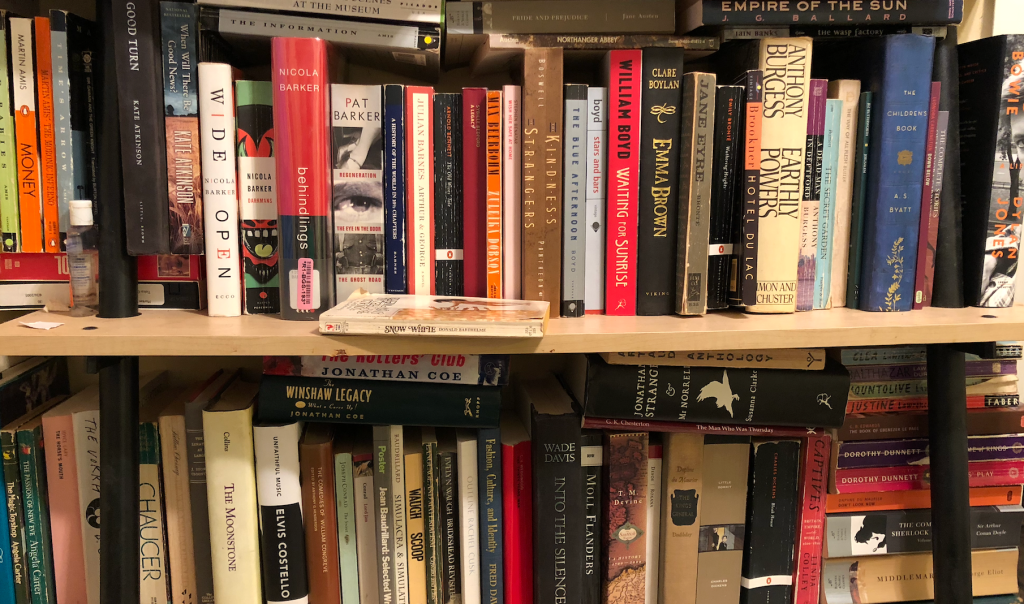

In elementary school, I went through a phase of reading a bunch of dying girl books. They weren’t horror stories (those came a bit later) or war books (though, those often surfaced at the same book fairs). These were specifically books about precocious girls struck down in the prime of sophomore year or just weeks before senior prom with severe, often-presumed terminal illness. The titles (Six Months To Live et al) were never subtle and always rendered in a dramatic script over a photorealistic image of some terrified girl with a fashionable spiral perm (doomed to chemo in chapter three) or a desolated couple in matching Jordaches and wedge haircuts locked in a grief-filled embrace in what could be a cemetery. You could buy them at the book fair and sometimes in the small YA section at the Roses on Merrimon Avenue, and if you were about ten years old, you could finish 1-2 on a rainy summer afternoon while stretched supine on your bed listening to the thunderstorms roll over the lake.

I do not know how many dying girl books I read during those summers around the fifth grade, only that by the time I got to It, a couple years later, I knew Pennywise was infinitely less terrifying than an ominous nosebleed the morning of 9th grade cheerleading tryouts.

Sick white girls were in the movies too, though I think the too-young-to-die thing really peaked in the 1970s. Probably with “Love Story,” but “Ice Castles” is in there too, for it’s terrible tragedy and heartrending recovery. I saw “Ice Castles” on cable. Multiple times. My favorite childhood dying girl movie was “Six Weeks,” a film in which a wealthy twelve-year-old dies of leukemia joyriding the New York subway in 1982 after starring in “The Nutcracker” at Lincoln Center after exactly one rehearsal. It’s an absurd, impossible plot point, so absurd that I’m sure the Make-A-Wish Foundation would rather I not remind the world that this film exists.

Dead girls have always been a weird, upsetting, much-discussed cultural fascination. But dying girls have their own special place in the canon. Consider the consumptive heroines of the 19th century with their tubercular pallor and blood flecked-handkerchiefs. The girls wasting away from heartbreak, from madness, from vampire bite, from scheming Europeans in Henry James novels. All those tragic sopranos. All those beautiful doomed heiresses and courtesans with a heart of gold. Easy to love because you will not have to love them for that long. Most of the time those stories weren’t really about the dying girls, but the people (mostly men) around them who got to react to their deaths and keep going.

The dying girl books of the 70s and 80s were a different thing. The protagonist usually survived the tale, for the simple, narrative reason that the books were written in first person. It was the friends/love interest she met in treatment that wouldn’t make it. If I were a smarter person, or had actually gone to film class in college, I might note that a raft of dying girl books slid in at just about same time as peak teenage slasher movie. What is a dying girl but a final girl, seemingly doomed from the start, yet almost always prevails by wit or baseball bat or lucky liver transplant, while her love interests/best friends/soulmate she met in the hospital dies brutally in chapter seven, from a chainsaw or maybe a rogue blood clot. The film ends with the killer neutralized; the books usually end with remission. But if there’s one thing that cancer and, say, Michael Myers have in common it’s their perpetual availability for a sequel.

Where do people go after dying girl books? For me, it was Middle School. Gothic and horror novels. Plenty of dying girls there too (what is Flowers in the Attic if not, what is Wuthering Heights if not). Literary fiction has plenty of dying girls as well, even if the girls aren’t girls and the deaths happen way off the page and sometimes the death, if little enough, is just a metaphor for orgasms.

Whatever appetite I once had for literal dying girl books had mostly frittered away by the time I hit puberty, which is a good thing, because it probably held off my crippling hypochondria until WebMD and illness-based message boards were invented, even if I still kind of, sort of secretly believed that seeing “The Nutcracker” in New York City would maybe result in my immediate demise.

I went to New York this past weekend, by the way, still rattling about in the throes of a health-related panic attack, and tried not to count the flutters in heart palpitations or worry that the bruised to touch feeling on my right rib might signal incipient liver failure. I went to some parties (irony or denial?). I bought a floral velvet coat that made me feel like a cross between a decadent poet and the lady who teaches life drawing at your local community center. I had a good time. By the metrics of dying girl books, I neither had a prom date or an audition for the dance team, so I figured I was probably safe. But I’m increasingly convinced there is not a protocol or a drug (legal or semi-)that will make me feel safe.

That’s reasonable, I guess. Look around at the world. I am at an age where lots of people I love have to worry about chemo and transplants and rogue blood clots. It probably goes without saying that they aren’t sixteen-year-old girls. They don’t get described as shockingly young or having their whole life ahead of them, even though youth gets a new definition at every birthday and a whole life in front of you just feels like matter of perspective. We’re all dealing with this in different ways. Anxiety. Denial. Keto. Blood pressure meds. The realization that, in health, there are causes and effects, yes, but they are not distributed equitably. The thing about mortality is that, at some point, we all get to be the protagonist in a dying girl book, though in real life we might not get to narrate the last chapter.

I don’t worry so much about that part. The end, I mean. It’s the unknown in between that gets me. And I’ll tell you something true: if you think that actually going through weird and traumatic medical shit will in any way inure you to fear of weird and traumatic medical shit, I can get you a good deal on a nice bridge over the East River. The pain is real. It persists. It changes and twists and does it’s best to confuddle. I know there’s coping and there are strategies. I know inspirational tales and great success stories. I also know what it feels like to smile through a day, pretending like you’re not waiting for the other shoe to drop. Fake it until you make it, right?

Do kids today do dying girl books? There was that John Green book I meant to read. I’m not really up on today’s YA. My sense is that it involves a lot of wizard dystopias, sexy fairies, and mean girls on social media. This all sounds like a lot more fun than Too Young To Die. Maybe I was born at the wrong time. Or maybe I should have hit a different section at the Book Fair. (How are you dragon people doing with the anxiety these days? Better? Worse?) Maybe I should start over. Check in on the sexy fairies. Developing a wing fetish might be personally embarrassing but is perhaps preferable to worrying myself sick. Literally.

The dying girl books were never my favorites anyway. They were a phase I went through. They were a way to pass time and wait for the storm to end so I could get out, go to the pool, and thrill, once again, at the infinite possibility of simply being alive.

Maybe this is just a phase I’ll grow out of too.