Dove Anderson smells like chlorine. The scent surrounds her. Toby is astonished he hadn’t noticed it before. Not that he’s ever been this close to Dove Anderson. Close enough that can see the clumps of mascara over her fish, bloodshot eyes. Close enough to see the side of a pale breast unencumbered by bra through a gap in her blouse.

She reaches into her blazer and produces a silver blister of nicotine gum. “You want? I’m supposed to quit smoking so they don’t expel me.” It’s unlikely she’d be expelled; Dove is a state champion swimmer, Most Likely to Win An Olympic Gold, according to the school newspaper, and recently awarded an athletic scholarship to Stanford.

She forces the gum into his hand. Hers is cold and clammy. She might be a mermaid. That would explain things. He checks for gills, but sees only hickeys. General consensus finds Dove the hottest girl in the school. Toby cannot see the appeal. General consensus also finds him to be priggish, obsequious and almost certainly homosexual. On these points, general consensus is largely correct.

“I don’t smoke,” he says.

“Give it time. In the meantime, these are for Chaz. He needs to see you.”

“I have a Latin test.”

“Ms. Davis is out. You’re watching “Clash of the Titans.” Coach Cartwright is subbing.”

Toby glances back toward the door of the Latin classroom, where a quarter of the Varsity Lacrosse team is smacking the asses passing underformers with their remedial math textbooks, to the obvious delight of Coach Cartwright. He shudders at each slap and every whimper.

“Chaz is in the Spiral.” She leans closer so he can hear the smacking of her fish lips. “He says you owe him.”

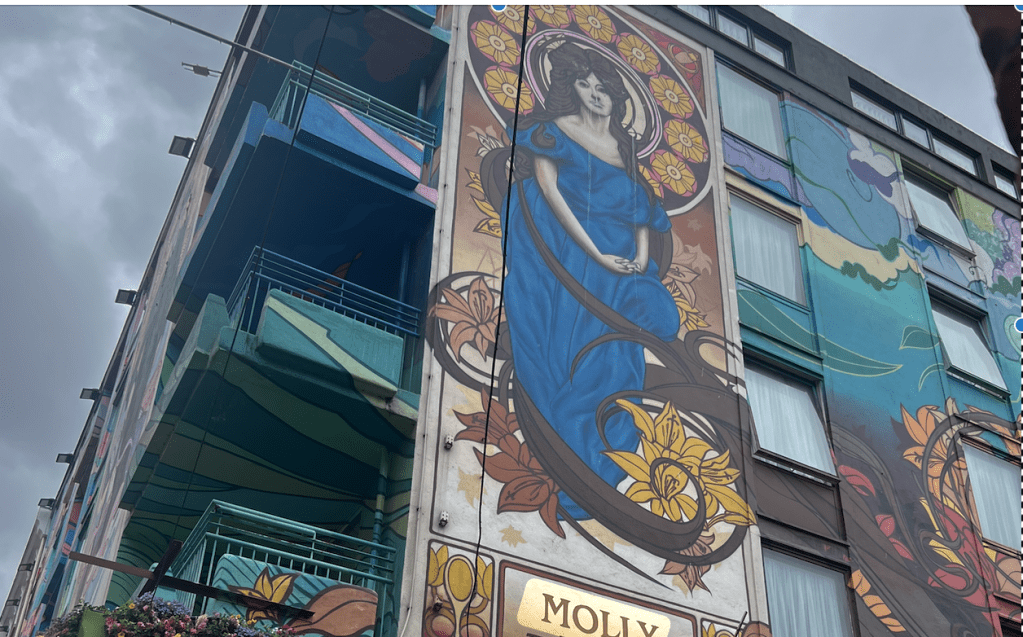

Dumbarton Hall was built in 1905, seven years after the founding of Westmoreland Academy and three years before its namesake perished in Africa. No further information exists in reference to Richard Wilberforce Dumbarton’s untimely passing, however an anonymous hand had scratched a hypothesis—fucked to death by an elephant—onto the bottom of the plaque by the front door.

The seventy-six treacherous steps of the Dumbarton north stairwell are filthy, reeking of both the wrestling team, whose coach forces regular runs of the so-called Death Spiral and the seventy-odd pubescent boys who reside within. The first time he ever entered the hallway, Toby walked directly into a fecund slather of shit, which might have come from, Bob Geldof, Mr. Beekman’s incontinent Irish Setter, or from Jim DeStuzzi, a fifth former whose sense of humor ran famously scatological.

Chaz perches on a stone window ledge, blowing smoke out of a slit-shaped window, somewhere around step fifty-two. Toby’s breathless with effort and barely acclimatized to the smell. He breathes through his mouth.

“Poor form,” says Chaz. “No wonder you were cut from wrestling.”

He blushes at the mention. He failed at a forced run by on the first day of practice and projectile vomited all over the one of the Liams, who promptly called him a pussy and punched him in the gut. The coach found Toby rolling on his side, eyes stinging with tears, covered in the contents of his own weak stomach. He recommended Wilder either man up or get out. Toby spent a night hiding out in the infirmary and then signed up for afternoon art workshop, where he’s since tried to look tough while sketching in the grass outside the studio. He finished four drawings, each one inspired by different scenes from “Atlas Shrugged,” his favorite novel. Mr. Lymond, the art teacher, called them “provocatively puerile” but it sounded like a compliment.

“Living dangerously, aren’t you?” he asks Chaz. “Smoking out in public like that.”

Chaz shrugs. It comes off like an elegant twitch. Toby hopes he’ll do it again, so he can learn how.

“Imagine how fast one would have to sprint to figure out who is smoking. Now imagine the physical condition of our esteemed faculty, I’d say I’m pretty safe anywhere over the second floor of this malodorous tumor.”

Toby leans against the iron railing and casts a vertiginous eye down the center of the spiral. He sways and feels Bolger’s hand on his shoulder.

“The secret to the death spiral is the secret to life, old man,” says Chaz.

“Don’t look down?”

“Au contraire. Most of life’s greatest pleasures can be found in or around the gutter. The trick is you mustn’t be afraid to fall.”

Toby imagines his head hitting the cement landing, his skull shattering. He shudders and pulls the gum from his pocket. “Dove said to bring you these.”

“Like I’d be expelled for something so pedestrian as smoking” Chaz punches a piece of gum through the back and tosses it into his mouth, without discarding the cigarette.

A steady drizzle of rain drops from the leaky turret through the center well of the stairway and collects on the stone floor beneath. A trio of boys skitters in over the threshold, cursing the puddle.

“This building,” says Toby, in slant imitation of Bolger.

“Complaining about this place is one of the rare perks of living in it. You’ll understand when you move in.”

Toby chuckles. “I’m quite happy where I am, thank you.”

“Bollocks. You’d sleep in Kinsella’s closet if he’d let you. Speaking of–” He flicks his cigarette butt into the rain and slides off the sill. “We have business. Onward and upward! ”

Chaz takes at least two steps at a time and reaches the summit in plenty of time to cluck at Toby’s desperate scramble. When the metal door at the top landing opens, Toby enters past a single word scratched into the brown paint.

VALHALLA

Once upon a time, getting assigned to fifth Dumbarton—a cramped fetid attic repurposed into eight dorm rooms when Westmoreland Collegiate went coed in 1979—was seen as punishment. It was where they kept the worst students, the troublemakers, the weirdos, the boys likely to withdraw on the grounds of self-loathing and despair. Ron Breedlove, one time class president and current head of the board of trustees was said to have originated the nickname Valhalla for Losers sometime after sending one of its former residents to the hospital with two broken ribs and a busted spleen after things got a little manic during one of Westmoreland Collegiate’s traditional hazing rituals. The name stuck.

But then Reverend Pete developed a rare lung condition he claimed came from living in Fifth Dumbarton’s hallmaster’s apartment and it was easier to raise money for new football field lights than asbestos remediation. Thus, Valhalla became the only hall on campus without immediate adult oversight. The old faculty apartment was converted into a private common room and larger-than-average prefect lodging. Valhalla, transformed, became the VIP section, inhabited exclusively by upperclassmen, in particular, the shaggy-haired, swaggering lords of the sixth form, whose spectacular indifference to the Westmoreland Collegiate Handbook of Student Behavior was rumored to be matched only by generosity of their family contributions to the Annual Fund.

Toby hadn’t known anything about Dumbarton or Valhalla or the boys that lived there when he filled out his application to Westmoreland Collegiate. He had just been a fifteen year old who had lost his mother and his faith in Jesus Christ more or less simultaneously and was certain that to stay in Eastern Kentucky would be a fatal mistake. So he’d filled out the applications and convinced his father that a son in an elite boarding school might add a dash of real class to Big Bud Wilder’s fiefdom of Ford Dealerships and spare them three more years of awkward dinner conversations.

Aunt Ivy drove Toby the two-hundred odd miles to campus. They goggled at the wide green lawns and the picturesque institutional Anglophilia. Toby felt almost light-headed at the musty scent of privilege wafting through the halls and stamped into every object adorned with the school crest. These students were obvious natural aristocrats. These were future leaders. They were his people.

His dorm room was in Phillips Hall, a clean, midcentury rectangle with large windows and air-conditioning, but Toby spent his in-betweens admiring the horror film matte backdrop that was Dumbarton Hall. By then, he recognized the demigods that dwelt beneath its gables. He’d learned their mythologies and practiced daily devotions. He took on rituals of self-improvement. He overheard the flushed chatter of starry-eyed girls outside of morning convocation and secretly felt kinship with them.

For didn’t he wish it was he and not Mary Ellis Culpepper that received a tender massage from Dave Nadalski in morning convocation? And didn’t he blush when Chris Kinsella, accidentally brushed touched Toby’s arm in Chapel when he was trying to fetch his anorak. He was guilty as the underform girls of stealing glances at Alex Stavros and Corbett Coleman and Oliver Eberstrom as they dried off by the pool after Swim meets. And he woke, sweaty and spent, from countless dreams of Chaz Bolger, the living, breathing, horrifying incontrovertible evidence that Toby’s now undeniable attraction to boys was not just a dirty little phase he passed through on his way out of the hills of Eastern Kentucky.

One October night, scarcely a month after Toby’s matriculation at Westmoreland College, he ditched the Harvest Mixer and set out into the woods by Rowing Lake with two Freshman girls, a half-Hungarian diplomat’s song, and a backpack full of fruity wine to flout the school handbook. Respectively foolish and harmless, Toby’s companions would be unlikely to judge should his first attempt at drunkenness end in vomit, humiliation or both. He chose something peach flavored and fizzy. Its effects were dizzying. He finished half the bottle in a few heroic and lounged against a mossy log to let the clear, cool October night wash over him.

Sometime in that spinny haze, the Lords of Valhalla emerged across the clearing accompanied by several field hockey players with expensive names. They offered up some good-natured abuse to their younger, drunker classmates and situated themselves on the rocks by the water’s edge. Pink Floyd wished you were here from the unseen, tinny speakers of a boombox. The clearing wreaked mystery and, as he later realized, marijuana. Valhalla remade the landscape into exciting and terrifying. Toby felt high off their nearness

He thought he might be dreaming when Chaz stood and stepped over the leafy ground to lie beside him, his head against the same wooden pillow. Show me what you see, so that I may look as content as you.

Toby replied with some mumbled nonsense about stars. Because how can you explain to a God what it is to be in the presence of divinity.

“I’m Chaz, by the way,” he said. “The lads tell me you’re Wilder, Tobias. From Kentucky. Horses or coal mines?”

“What?” asked Toby.

“Which part of Kentucky? Horses or coal mines. We’ve made a bet.” He nodded toward a pair of giggling double Marys.

“Mines,” says Toby.

“I knew it.” Chaz sat up and called across the clearing. “Horses.”

There was a smattering of applause and someone turned up the music.

Chaz settled back against the stone and shook his head. “Always say horses.”

“What if my father owns the mines?”

“Especially if your father owns the mines.” Bolger offered a cigarette. “Does he?”

Toby shook his head. “He owns four Ford dealerships.”

Chaz laughed. “That tracks.”

Not knowing whether to appear flattered or indignant, Toby settled on reverent and moved ever so slightly closer to Chaz’s arms. Chaz held forth on aesthetics and uppers and upperclassmen and how he’d volunteered for another year of high school because he’d bungled his A-levels back home and America was full of surprises. And it seemed like Chaz was moving closer so it seemed like it wouldn’t be the worst idea to let his fingers touch the side of Chaz’s face. After all, he was drunk and spinning and if Chaz responded with a punch he would be halfway numbed to it anyway, and if he didn’t then, then maybe a kiss, a chaste, close-mouthed kiss, but a kiss nonetheless. Toby raised his hand and Chaz pushed Toby away. No insults, no violence. Honestly, the last possible reaction he might have expected.

“I’m not gay. But you are, aren’t you?” Chaz dusted himself off and lit a cigarette. “And you just won me fifty dollars. “

It took a moment to process. And by the time the stun wore off, Toby heard Chaz crow about his victory to his fellow sixth formers. Toby staggered off to puke over a downed log. He reckoned he should be glad to be breathing and whole. He swore off alcohol for life and tried to face the unfathomable horror of what his life would be like now that everyone knew. His father would find out. The school would expel him. He would be cut off, turned out, left to starve on the streets of Kentucky, where he would be scorned by society, beaten by his chinless cousins and spend the rest of his days denied access to the halls of wealth and power to which he so hungrily aspired.

Sometime later, he heard the sound of footsteps.

“Go away.” He squeezed his swollen eyes shut.

“You really think this is necessary?” asked an unfamiliar, southern-accented voice.

“Well, I feel bad, you know? Not really in me to leave a man down.” Chaz loomed over him. “Listen, mate. We really need to get you back to your dorm. Can you stand up?”

“No need. My life is finished,” says Toby.

“Bloody Stavros and his bloody wagers.” Chaz kneels down. “Do you think we can carry him?”

Toby felt his legs lifted and then dropped.

“I dunno. He’s sort of fat.” said the other boy. “We might need Oliver.”

“Oliver is carrying your drunk girlfriend.” Chaz sighed and turned back to Toby. “Look, I really am sorry, mate. Terrible prank. Let us make it up to you and help you back to campus.”

“I’d rather die. Just leave me here to die.” Toby sniffled and curled up tighter.

“Is this because of the gay thing? Because really, it’s nothing. Coleman here is enormously gay. And he assures me the student body is quite homosexual all told. A quarter at least.”

“I’d put it more like a tenth, honestly” says Coleman. “But it’s not nothing.”

“You can’t stay out here in the woods,” says Chaz. “You have to come back now. Will you come back with us?”

Toby felt someone pulling at his arms and a hand at his lower back. He found himself reluctantly upright and standing between shame and desire, or more specifically, between Dave Nadalski and Chris Kinsella, as they half dragged him up the perimeter trail and back to Phillips Hall.

He suffered through the next morning’s Sunday Chapel, certain he would face immediate scorn, probable expulsion, and possible smiting from the Lord himself, but the heavens kept quiet and no one said anything. No one even looked at him.

Afterwards, he was summoned by Chaz Bolger. He followed the older boy around to the back of the chapel, where he found the rest of Valhalla in daylight, removing their ties and jackets. Most seemed indifferent to him, save Chris Kinsella, who gave a little shrug and said, “Sorry about your friends.”

Toby squinted, as if surprised to hear he had friends at all.

“The kids with you last night,” he said. “They got busted trying to sneak back into Turner Hall after curfew. I’m on their honor court tonight. Pretty sure I can’t save them.”

Toby didn’t care about the kids in the woods. “They weren’t my friends,” said Toby, and considered adding a Good riddance to punctuate, but worried it might be overkill.

“Kinsella’s our hall prefect,” said Chaz. “Our inside man.”

Toby nodded, while the other stared at him with open amusement. “Should I be thanking him?”

“Thanks will not be necessary,” said Chaz. “ We don’t like for our friends to suffer. And as you are a friend, we’re sure the feeling is mutual, should we ever need your assistance.”

“What kind of assistance?” asked Toby.

“The kind necessary to navigate delicate circumstances.” Chaz stepped closer and casually ran a hand over Toby’s lapel. “ As I’m sure a man of your unconventional predilections would certainly understand.”

Kinsella rolled his eyes and sighed. “I’m walking away now, Bolger. Plausible deniability.”

Toby turned to watch him retreat over the grass, coppery hair shining. Toby had always admired how Kinsella always looked as if he should be sailing a yacht, which for all he knew, was a thing Kinsella did in his spare time. But on that day he was too distracted by I am still here. Chris Kinsella left but I am still here to fully appreciate the proposed blackmail. Not that it would have mattered. He would have done anything they asked.

As a seniors-only hall, access to Valhalla was strictly off-limits to underclassmen and pretty much implicitly forbidden to anyone not invited by the residents. It was also expulsion-level forbidden to girls—as was all of Dumbarton Hall, though there had long been rumors that girls made use of the fifth floor common room and the boys that occupied it.

Toby wonders whether the campus janitorial staff avoided the hall by choice or by dictum as he passes under the spidery wires of a deactivated smoke detector and into the common room, an odd angled mildewy nook stuffed with several sprung, smoke blackened sofas. Alex Stavros paces by the window. Corbett Coleman leans against the door frame. Dave Nadalski lounges on the sofa under a blanket, which stirs and grows skinny legs as Chaz approaches.

“Gents only,” says Chaz.

“Go fuck yourself, Bolger,” say the legs.

“Unless you would like your lovely lady friend implicated, I suggest she make herself scarce. Like out of the building scarce.”

Mary Ellis Culpeper wiggles out of the blanket and half-heartedly fixes her hair. Like most of the girls favored by Valhalla, Mary Ellis dresses in a style that barely passes dress code—cheap knit skirts and sloppy misshapen sweaters and ugly men’s shoes. Toby finds it appalling. At least one of his (thus far anonymous) Letters to the Editor of The Westmoreland Collegiate Monthly Post had been on the subject. “Given the traditional attire required for male students, female students should not be given such leeway in classroom dress. They should absolutely be required to wear attractive, though not showy, shoes, a nice, tailored skirt in a modest length, a blazer—not too mannish—or perhaps a sensible twinset. Pantyhose would be preferred. Given that grooming standards are enforced for Collegiate men, it seems reasonable that attractive, well-kept hair or tidy up-dos for its women should be strongly encouraged.” He’d been quite proud of that one, and had thus been aggrieved to find it mercilessly mocked. Even Chaz had said something about it, it seems we’ve a classmate with a fetish for teenage girls done up like Nancy Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. As a devoted fan of both ladies, Toby had struggled to understand why that was a bad thing.

Certainly Mary Ellis Culpeper could only be improved by trying to be more like the former first lady. As it is, she tugs at her sagging tights like some derelict hooker and glares at Chaz.

“If it makes you feel any better, love, we also kicked Kinsella out,” says Chaz.

“I’m not your love, Chaz,” she says, and pushes past Toby on her way out the door.

When the door clicks shut, Coleman sinks onto the arm of the sofa. “Why is this sad fat child here again, Bolger?”

Chaz smiled and said what he’d said every time Toby had been called for a favor.

“Because Toby is very clever and extremely talented. He is clearly the only man I could imagine for the job.”

The first time he heard it Toby believed that the great and beautiful, all-seeing, all-knowing Chaz Bolger had made a mistake. For though he filled idle hours with an elaborate fantasy life full of grand heroics and brave adventure, he was a shameless coward. His affection for rules nearly equaled his aversion to risk and would have long sent him screaming away were it not such a fawning desire to please that he’d accept whatever task they gave him—disposing of pharmaceuticals, pilfering taxi vouchers from the Dean’s office, outfitting Mary Ellis Culpeper from his own closet so she might slight unnoticed into Valhalla between classes, providing Oliver Eberstrom with a clean supply of urine for drug testing —without argument, basking in the comfort of being needed by creatures so much greater than himself.

“Tobias is going to help us arrive at a solution to the Oliver problem. Which will hopefully keep all of us from getting arrested.” Chaz gestures down the hall. “If you please.”

Toby follows, nervous at potential horrors—guns, stolen goods, dangerous animals, a dead body? Couldn’t be. In fact, when Chaz opens the door into Oliver’s small room, the first thing Toby sees is the pale hand of a prone body under a plaid comforter. A woman, older than they are, with messy blonde hair half obscuring her face. Toby thinks a prostitute. He glances over his shoulder and sees Eberstrom’s glowering, Byronic face and thinks. Oliver Eberstrom hired and murdered a prostitute.

“Before you freak out: she’s not dead,” says Nadalski.

Chaz brushes the woman’s hair away from her forehead. The face appears unfamiliar at first, shadowed with smudged make-up and slackened with sleep, but once the features start to coalesce Toby nearly jumps when he realizes it’s the Latin teacher.

“That’s Miss Davis.”

“No shit, Sherlock,” said Stavros.

“Isn’t she a nun?”

“Ex-nun,” says Chaz.

“Her name is Denise.” Oliver sniffs –it takes Toby a moment to realize he’s actually crying– and rubs at his killer’s face. “And she’s the love of my life.”

“Jesus Christ,” says Coleman.

Toby blinks. “How did this happen?”

“We’re getting married,” says Oliver. “As soon as she’s conscious.”

“Why is she unconscious?” asks Toby.

“She came up last night after lights out the way she normally did. And we were hooking up the way we normally do and she said she wanted me to run away with her, to go somewhere else, like maybe Orlando and start over and I was, like, sure let’s do it, because my she’s my bright spot andI don’t have a lot of options— “

“He’s on probation,” says Stavros. “He got busted last summer for possession.”

“Hence the urine tests,” says Chaz.

“And you’re also fucking seventeen,” says Stavros. “And what is she, thirty?”

Oliver hugs at his knees. “She was so naïve. So inexperienced. She says she’s never been in love before. So I told her we had to wait, at least for the end of the semester, then maybe I graduate. But she kind of flipped out and started crying and we drank some vodka. And I gave her a sleeping pill.”

“Which he does not have a prescription for,” says Stavros.

“I bought them off of Jim DeStuzzi.”

“For Christ sake,” says Stavros. “Of all the dumb shit, terrible, fucking decision-making, Oliver.”

“Chill, Stavros,” said Dave Nadalski. “If we wanted nagging, we would have told Kinsella.”

“Kinsella would have called an ambulance first thing this morning, which is a thoroughly not-stupid idea.” He kneels in front of Oliver. “Look, I don’t know what the age of consent is in this cracker-ass state, but this is basically statutory rape. You get that, right? You tell them she did it. They’ll believe you. Because you’re a kid. And she’s your teacher. My Dad used to be a DA. I know what the fuck I’m talking about.”

“It would look better if she weren’t in a coma,” says Nadalski.

Oliver looked up, startled. “She’s not really in a coma, right? She’s just asleep, right?”

“I still say go with statutory rape,” says Stavros. “So long as she doesn’t die, that will probably take some of the heat off the possible murder charge.”

“Stavros, as much as we all appreciate your firsthand knowledge of criminal law, why don’t you bugger off? You’re not helping.”

Oliver sobs into his hands. Coleman offers calming platitudes and a gentle hand in Oliver’s black hair, which the other boy brushes away with a muffled slur between sobs.

Toby tries to decide whether he’s feeling shock or horror or righteous indignation at the sight of Miss Davis, kindly, appropriate, polite, Miss Davis, she of wholesome conjugations and hiccupping giggles at her own Latin puns. She of nervous declensions and anxious manners, who matches her shoes to her pastel cardigans. She, who once ran sobbing from the classroom after hearing Audrey Weinberg say the word vagina. Miss Davis was the faculty sponsor of the Young Conservative Club, which Toby planned to assume leadership of, once he was free of Chemistry tutoring on Thursday afternoons. It is impossible to believe that she had not been vilely abused by Oliver Eberstrom with his beastly manners and frayed posters of Jim Morrison and marijuana plants hanging from his walls. And yet, Toby finds it equally impossible to be angry, truly angry at beautiful, dark Oliver Eberstrom with his glorious shoulders and his pouting lips. Who could blame Miss Davis? Certainly not Toby.

“We have to get Ms. Davis out of Oliver’s room and into a safe venue from which emergency services can be called.”

“And we have a finite amount of time before someone figures out Ms. Davis is not just in bed with a stomach flu. Then Oliver’s busted and we’re all busted and Sayonara Valhalla. Even if I don’t get expelled, I only have four more months until I’m out of here for good. I’m not going to spend it in a dorm with a bunch of fat virgins,” says Nadalski. “No offense, Wilder.”

“You should be more worried about trying to find a lawyer when this thing goes tits up.”

“Fuck off, Stavros.”

“We do have a plan.” Chaz sighs. “What do you know about the hole, Tobias?”

It is a myth. That’s what he knows. It is another extravagant detail attributed to Valhalla that cannot be credited. A five story system of ropes and pulleys that runs somehow from the basements to the very heights of Dumbarton Hall would be impossible, to say nothing of inefficient. And yet, after today, he barely has a moment to register surprise when Nadalski kneels to peel back the carpet and pry open a square of floor, only slightly larger than the Black Sabbath album cover Eberstrom has tacked to his wall– maybe 15 inches square– and shrugs “Might work.”

“She’s too big,” says Stavros. “Her ass alone—“

“Her ass is perfect and you’re a monster,” says Oliver.

Toby peers down between pipe and support beams to see a brass handle affixed to a piece of asbestos ceiling tile. “Jesus. Is it like that all the way down?”

“At the bottom it comes out over the work table in the maintenance room. Somebody has to open that one bottom up.”

“How do you get in the maintenance room?” asks Toby.

“Ms. Davis stole a master key so she could get up here at night.”

“Which brings us to you,” says Chaz. “We are a bit preoccupied with the mechanics up here—all the ropes and harnesses and whatnot– and we need someone to manage the scene below, to treat with the other students, explain to them how they should stay out of their rooms for the next few hours before lunch, while we gently—very gently– lower Miss Davis to a more comfortable location.”

“But why me?” asks Toby

“I told you before,” says Chaz, “because you’re very clever. You command a lot of respect among the lowerclassmen. The fate of Valhalla is in your hands, Tobias. It is you and only you that can save us all.”

Toby glances at the crowd and their seeming solemn faces. He looks about the filthy, crowded room with its dark paneled walls and the ragged curtain of blankets hanging immediately above Ms. Davis’ pale inert body. Her hand shakes, slightly. He worries she might wake and see him standing there and see him seeing her in Eberstrom’s bed and suddenly that seems almost worse than the rest of it. And at that he feels the first stab of treacherous panic.

“You’ll do it, won’t you?” asks Nadalski.

Chaz smiles. It’s dazzling. “Of course he will.”

Toby returns to class, specifically English II, where he uses the margins of his paperback “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” sketch out a loose diagram of Dumbarton Hall and the names of the boys in the rooms beneath Eberstrom’s–Teo Salazar, Sean Riddle, Roger Ames. Ames seemed congenial enough, though he’d never given Toby even a second glance. Riddle was haughty, sarcastic and famously suffered no fools. But Salazar. He shivered slightly. He’d been partnered with Teo Salazar in Chemistry at the beginning of the semester. In an effort to make conversation, Toby said something perfectly congenial about Salazar’s excellent command of English and how thrilled he must be at being able to escape his impoverished home country and come to the US. Salazar replied by asking for a new lab partner. Later Toby tried to apologize, explaining that he, himself, was from a backwater—Eastern Kentucky, actually—and how excited he’d been to come to a place as urbane as Westmoreland Collegiate and how he’d just imagined that it might be the same for a minority kid from somewhere in Mexico, coming to the United States for the first time—so no hard feelings, I really didn’t mean to offend. And that was how he’d learned that Teo Salazar hailed from Barcelona, grew up in Beverly Hills, and had an extensive vocabulary of synonyms for “hillbilly.” Since then, Toby avoided as many minority and foreign language speakers as possible, viewing them all as dangerously volatile and frightfully oversensitive to simple misunderstanding.

Toby worries his way into the path of Sean Riddle in the hall after class. The other boy greets Toby’s request to discuss a very serious and secret matter of real importance with a look of forced indulgence as they retreat into the semi-privacy of the hollow under the stairs.

Toby tries to appear casual, even indifferent, as he names the holy names Chaz, then Nadalski, and Oliver, you know, Oliver. He feels confident. He feels convincing. He feels like he is doing a fine job, but when he gets to the meat of the story, Sean raises a hand.

“You can stop.”

Toby sees that Sean means to leave. “Wait. This is important. I know you don’t care much for me personally, but this is not about me. This is about Chaz and Oliver. This is about the future of Valhalla itself.” Toby knows he has him. He uttered the totemic word. He’s forged an alliance.

“Valhalla?” Sean’s cold, suspicious expression warms slightly at this. His lip kinks in a half-smile.

“Yeah, Sean. Valhalla.”

“I figured they were just blackmailing you, but you actually buy their shit, don’t you?” Sean stares, eyes glazed behind his glasses, as the stairs rattle overhead.

“You don’t understand. Something terrible has happened. It’s not just about them. There’s somebody else that needs help.”

“Is that someone else you or the Latin teacher?” Sean asks, so loudly, that several other students glance over at them. “ There have been rumors about it since breakfast, And they’re, what? Going to try and lower her through the hole? God, that’s so fucking dumb. They’ve never managed to get anything up through the hole, except, like, one carton of cigarettes, one time. And that took about two days of planning and probably a hundred bucks of bribes. Mostly because Teo Salazar hates Oliver Eberstrom more than just about anyone else on campus except for—wait just a minute—you’re the fat racist redneck who didn’t think he spoke English, right?”

The word redneck drips over him. Especially the way Sean says it, like it’s not even an insult, but a fact. Toby thinks I hate Sean Riddle. I hate Sean Riddle more than anything else in the world. He summons Chaz’s face as a charm and tries not to concentrate on everyone here who knows everything.

“They’re going to get busted. And so will you.” Sean shakes his head and pulls on the straps of his backpack. “Seriously, man. You can do better. I mean, at least get blackmailed by smart people. Fifth Dumbarton is pure idiot all the way down.”

“Go to hell.”

The other boy shrugs off. “See you there.”

Toby breathes deep and counts to about thirty-six before stepping into the corridor. He sees Dave Nadalski standing by the exit door. He smiles tightly. Nadalski taps his watch face. Toby gives him a weak thumbs-up, before disappearing back into the stairwell, where he can cower in the gum-papered dust of the farthest corner and surrender to tears of absolute futility.

Later, he will say he had no choice. Later, he will say he knew all along what he would do. Later, he will brag about his full-throated, fully confident plan to inform against the boys of Fifth Dumbarton as a matter of principle. They were bullies and liars, he would say. Unapologetic rule-breakers. Entitled fools. And just because those things are true will not retroactively change the craven stutter that starts the betrayal when he slumps into the Dean’s office to report a terrible thing happening in Dumbarton Hall. And it takes a few minutes to get going, but once he does, the words trip out all over themselves and the Dean calls for the Headmaster and the Assistant Headmaster and now he has an audience so he adds details. He talks about extortion and hazing. He talks about bribes. He talks about Mary Ellis Culpepper doing perverted things under a blanket. He talks about Dove Anderson sending messages and drugs. And for good measure he talks about Teo Salazar participating in black market materials passing through the Dumbarton Hole. Even if it did happen just one time. It did happen. He’s about to accuse Sean Riddle of abuse because he’s on a roll and the Assistant Headmaster is scribbling furiously, but the Dean stops him, and says to the headmaster.

“Excuse me, Mr. Morris, don’t you think we should probably see if there is, in fact, an unconscious faculty member on Fifth Dumbarton?”

The headmaster hesitates, for a moment as if considering how many stairs he must climb to reach Valhalla, then nods, tightly, and waves a hand. “Yes, yes. Ms. Andrews. Of course.”

The Dean turns to Toby. “Thank you for coming forward, Mr Wilder”

Toby gapes, heart racing, flush with betrayal, feeling with each moment less like Judas Iscariot and more like Elliott Ness. He leans across the desk. “Did you need more information? I have more information. Five more minutes. I know things about some of the girls too. And I could show you where that woman is,”.

The Dean knits her eyebrows together. “That woman. You mean, Ms. Davis.”

“Peggy—” says the headmaster.

The dean shakes her head. “That will be all, Mr. Wilder. You have Chemistry this period, I believe.”

He shuffles down to the lab in a daze and tries to look triumphant at Teo Salazar’s scowl. Like the rest of the class, he starts at the sound of the ambulance and cranes his neck to see out the windows, but there are no views of Dumbarton Hall from the Chem Lab, so he waits until the end of the hour, when Salazar is met in the hallway by the Assistant Headmaster and directed upstairs.

Now, there is talk, lots of talk. He drifts into the dining hall on pointed gossip and idle speculation. He is almost at his table, when he follows a thread of his own name Toby Wilder. Someone said Toby Wilder turned them in. And the tremor of remorse is less than the peculiar pride at being talked about, at being talked about for a thing he has started to feel a little pride at doing. Enough pride that he barely registered the Who is Toby Wilder again? Isn’t he that fat kid from West Virginia?

There is shame in disloyalty, but power in toppling a regime. Toby revels from the front porch of Sunderland hall after lunch, enjoying his moment of glory from the seat of administrative power. He hears the scream closed behind him, the steps on the flagpole, and a familiar voice, shorn of affect:

“Horses or mines.”

Toby turns.

Chaz stood on the mat behind him. “Ask me. Horses or mines?”

He opens his mouth to say something cold and indignant. To put Chaz in his place. But he feels only sadness and disappointment and none of the things he wanted to feel. He clears his throat. “Horses or mines?”

Chaz pulls a squashed pack of cigarettes from his breast pocket. “Mines, of course. Figured you might have sussed that out by now” He strikes a match. It burns gratuitously, brilliant orange against the damp gray shrug of the afternoon. “But you Yanks think we all sound so posh.”

The door squeals again. The Headmaster barks out at the disrespect of smoking on the porch and the necessity for Chaz to remove himself forthwith to pack up his things and leave campus forever. Still he puffs on and it is not until the older man physically directs him toward the stairs that Bolger drifts into troublesome memory.

Toby feels hand on his shoulder.

“You did a good thing today, son,” says the headmaster. “ I won’t forget that. You have the kind of values this institution was built on. I’d like to encourage you to take on a more active role in student leadership. We need more kids that think like you.”

Toby blinks as Chaz disappears into the death spiral.

“Though we honor tradition, we mustn’t be enslaved by our past,” says the headmaster. “We must always strive to rise to the occasion. We must spurn those that would lead us to fall.”

The secret to life is the secret to the death spiral. Toby takes a step to descend the stairs, then pauses. You mustn’t be afraid to fall.

“Young men like you were born to rise,” says the headmaster.

“Yes, sir,” says Toby. “I believe I am.”