My Aunt Molly’s house always smelled like oranges, even when there were no oranges. I could smell oranges on the pages of the Chopin score she kept open on the grand piano in her living room. She always hosted the family on Christmas and Thanksgiving. I stole her cranberry chutney recipe and also her chicken curry. She always had Christmas Crackers, even when it was just Thanksgiving.

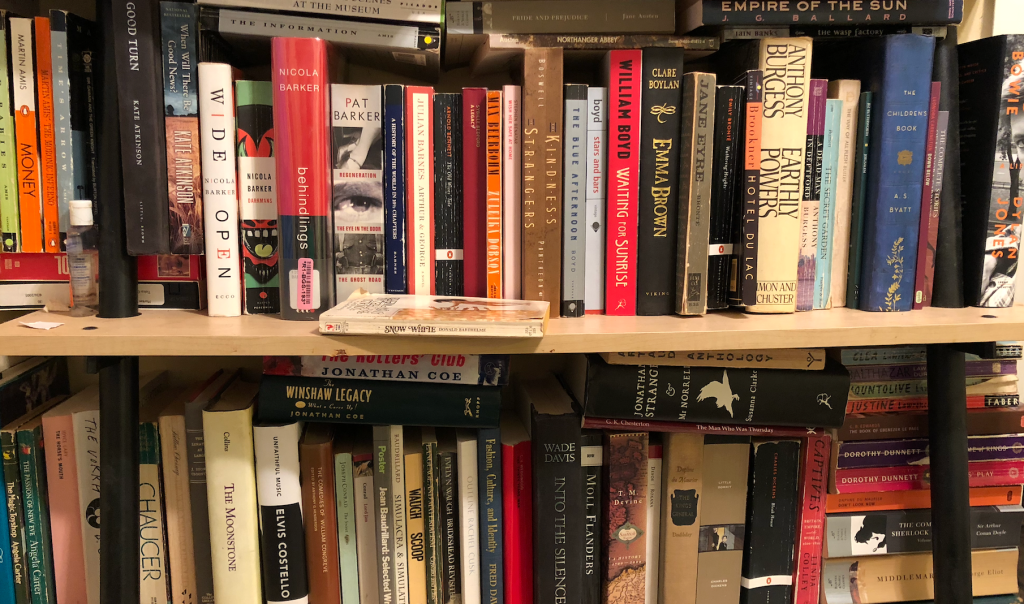

Molly liked Dickens. She would delight you with character names. She would conjure up obscure and possibly imaginary London locales with a few soft-spoken details. For years I believed she would periodically spirit away to do a shift at The Old Curiosity Shop. She never corrected me

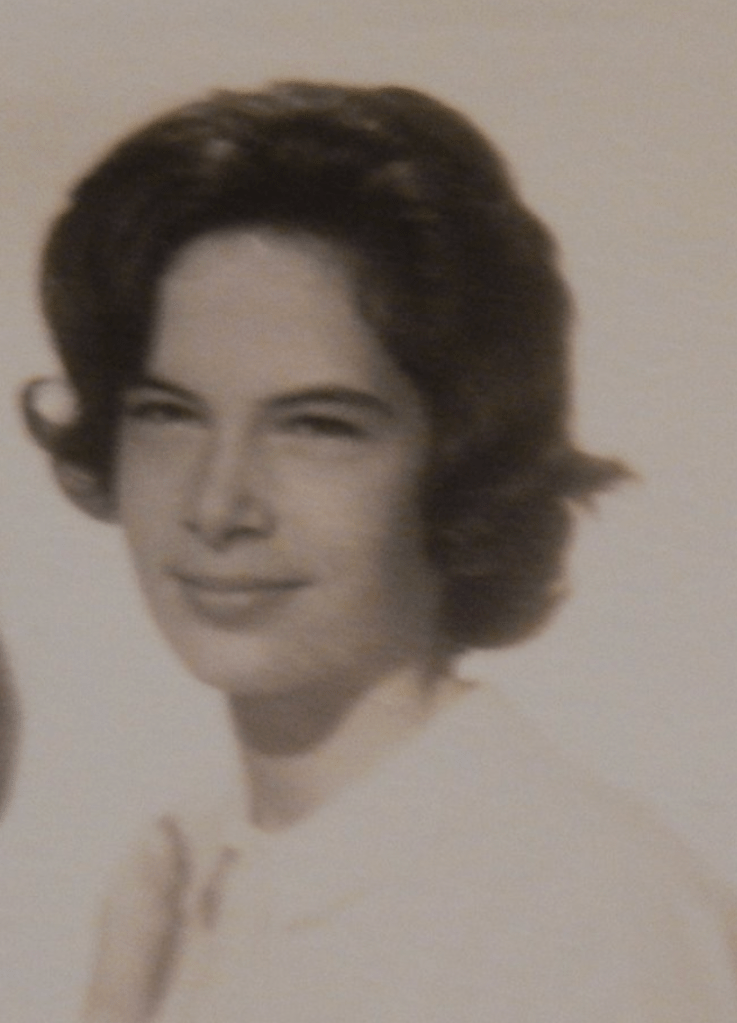

No one gave presents like Molly. She would root around in family archives and come up with tiny treasures: a great-great grandmother’s bit of petit-point, an old letter about William Faulkner, the best pictures I ever saw of one great grandmother, the other great grandmother’s beaded vanity kit. When I was fifteen, she gave me a vintage felt hat, sable gray with a fur trim, and I wore it until it fell apart. We shared a love of the weird bits, and she never stopped sharing. I always knew to open her envelopes carefully, lest I disturb the treasures tucked inside.

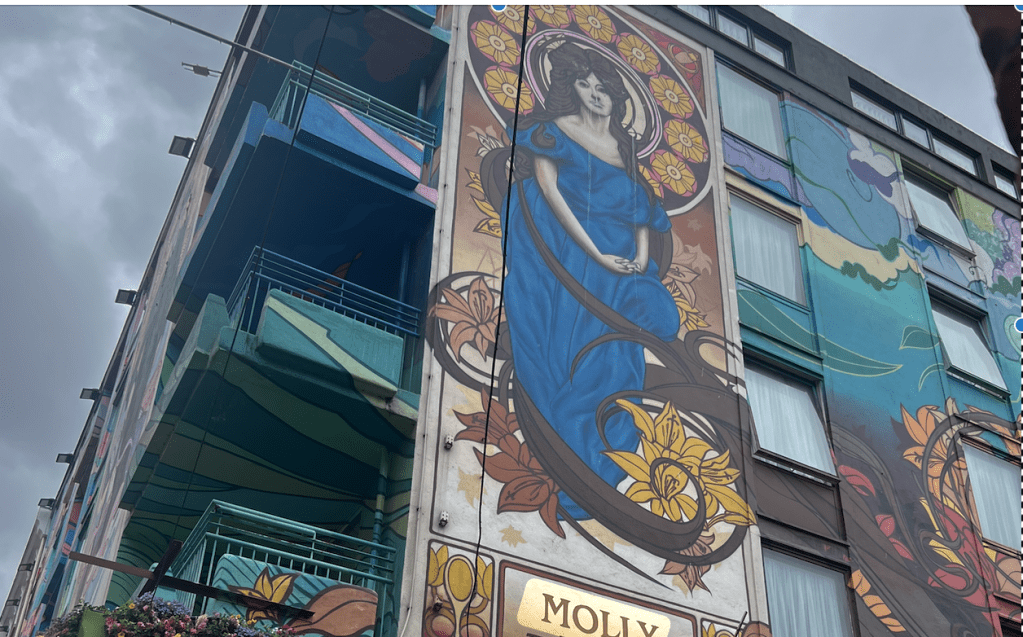

Molly opened a bookshop when I was a young teenager, which made her very cool, in my eyes and even cooler because she called it Bookends, which I loved because I was a Simon and Garfunkel fan (she was too).

At sixteen, she slipped me a brand new hardback copy of The Secret History with a wink, after a melancholy Thanksgiving. I read the whole thing that night and remember thinking that no one had ever pegged me so well with a book recommendation.

She’d always send the kindest, most thoughtful notes. Sometimes just an old postcard and a scrap of poetry. I sent her my writing sometimes. She gave me the most thoughtful responses. Kind and generous. I was excited when she started writing and writing seriously. We were a family of writers. And she was, in her own way, a star.

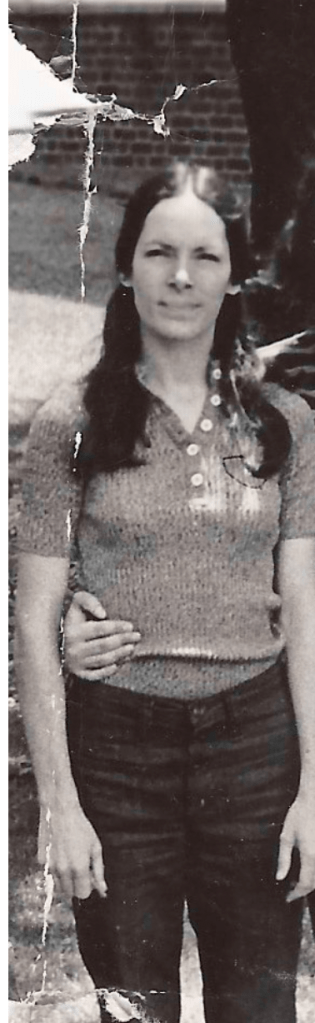

Molly was easy. A cup of tea. A glass of wine. At family gatherings, I could seek her out for a moment of solace. She moved to Asheville around the time I moved back. She was a seeker, a dreamer, both soul deep and light as air. She always had a wide front porch or a room full of windows. She made things, quilts and crafts, but also stories and verse. She enjoyed the excavation of family history and was brave enough to illuminate the dark parts, even when opening doors led to heartbreak, for the promise of clarity and grace, a scant glimpse of the numinous.

A friend, an advocate, a mentor, a professor, a woman rooted into each community lucky enough to welcome her. She had a gentle step and a soft voice. Like most wise people, she knew how to make an impression without unsettling the universe. She was stronger than most people realized unfailingly hospitable, polite, and unafraid to be wholly herself.

Family is family but some family feel like more than blood. They feel like a line to some part of you. A connection so true it can hardly be expressed. She never had to say it and maybe I should have. She was my father’s closest sibling, not just in age but in spirit and sensibility. I intuitively recognized the verse and meter of her searching, her sincerity, her faith in the power of things fragile and beautiful and bracingly honest.

Life complicates expectation and confounds intention. It is also heartbreakingly short. We don’t get to negotiate for stolen moments once the wheel is in motion. I didn’t get a chance to tell Molly all I wanted to. What she meant to me. Who she helped me become. All that she shared so selflessly with a community far larger and more vibrant than I’ll ever know. Things happen so fast, so stupidly, impossibly, breathlessly fast. I hope she knew how much I loved her. I hope she knows it’s a beautiful evening and the birds are singing by the pond and it sounds like poetry.

Slainte, Molly. I’ve still got that Emily Dickinson you gave me when I was thirteen.

I’ll miss you very much.